For a responsible use of Nordic Forests

OULU – Arctic forests are not doing well: growth is decreasing, cuttings are increasing, and in the last 20 years trees have gradually absorbed less and less carbon. Exploring the legacy of the ENI CBC northern cluster programmes, TESIM has decided to dig into one of the topics the programmes have extensively dealt with. Because the alarm for Arctic forests is high.

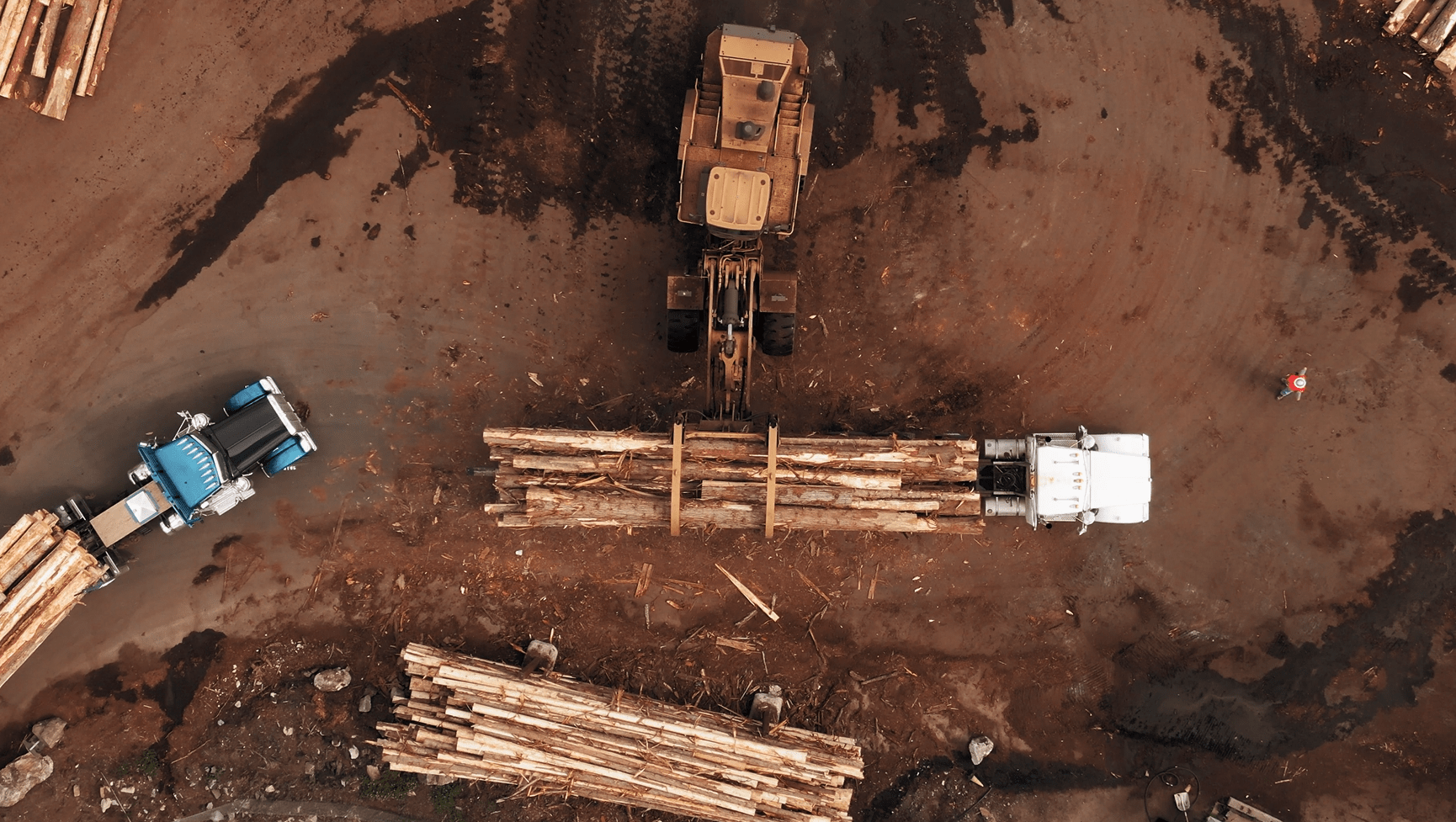

Finland is Europe’s most forested country, but in 2021 its land use sector – including forestry, agricultural, industrial, mining and housing functions – has become for the first time in history a net source of greenhouse gas emissions. “Forest are still net carbon sinks – says Päivi Merilä, research manager and principal scientist of the Natural Resources Institute of Finland – but from 2020 to 2021, in just one year, timber cuttings have increased by 11%”. Moreover, logging hits particularly young forests, with trees between 21 and 40 years of age. “As young forests are the ones preserving the greatest ability to bind carbon – continues Merilä – the result is a further increase in emissions”.

And here is the “great dilemma” of the green transition. The downshifting of fossil fuels implies increasing the use of natural resources like wood, and is therefore an extra drive to logging. To this, climate change adds other alarming factors like droughts, rising temperatures, spreading of fires and infestations. As a result, forests witness a serious decline in biodiversity. Today, a pressing question faces Finnish and neighbouring regions: how can this be reversed? How can economy be conjugated with the protection of natural resources? How can such a unique natural environment as Arctic and boreal forests – so important for the preservation of the biosphere as well as for the wellbeing of local societies – be used in a sustainable way?

Here is where the ENI CBC programmes have brought in their contribution, working across northern regions – often thanks to the extensive application of new technologies – to support not only the diversification in the use of forests and the identification of new business models beside timber cutting, but also the protection of biodiversity, the improvement in multifunctional forest management, the coordination between protected areas. Now that programmes are reaching the end of their implementing cycle – and a new programming period is not in sight because of the suspension of cooperation with Russia due to its military aggression on Ukraine – it’s time to look at the heritage they are passing on.

Let’s take the concept of multiple use of forests. Next to log cutting or reindeer herding, there is berry picking. The right of public access makes it possible for everyone to pick berries in Finland, and in recent time the market appreciation of these little roundish juicy fruits has increased, as well as awareness of their exceptional health-promoting properties. To favour the use of this non-wood forest product in Nordic countries, the ECODIVE project (Karelia CBC Programme) has researched forest vegetation and soil, producing an inventory of 68 edible wild plants and a study on soil types, to identify the most favourable sites for berry growth. The research has revealed that forest management and cuttings clearly influence the abundance of berries. “Forests should be managed so that not only trees, but also other plant species thrive – explains Maija Salemaa from the Natural Resource Institute of Finland, the project lead partner – Plant species create the basis for the diversity of the entire forest. Blueberries produce pie, but also support pollinating insects. Their presence has a comprehensive effect on the success of crops, and the sustainable development in the region”. Now, where do berries grow best, and why? Thanks to laser scanning, ECODIVE has identified in a scientific study the features of forests linked to locations of the highest berry yields. Prediction models have been developed to produce maps showing the most potential sites for bilberry picking. “In the future – says Päivi Merilä – models could be imported into forest planning systems, as we do for timber”. Today many owners start appreciating the multiple benefits of forests, including the non-wood products. Out of a population of 5,5 million people, Finland counts on 600.000 private forest possessors: if berry yields were to be integrated into forest planning, owners could evaluate a trade-off from loggings, when the moment comes to take decisions. “We need to change mentality – adds Hanna Leena Pesonen, sustainable development specialist – and to expand a global approach to forests as a source of timber and non-timber products, as biodiversity mines, as a resource for tourism and recreational activities”.

Let’s take the concept of multiple use of forests. Next to log cutting or reindeer herding, there is berry picking. The right of public access makes it possible for everyone to pick berries in Finland, and in recent time the market appreciation of these little roundish juicy fruits has increased, as well as awareness of their exceptional health-promoting properties. To favour the use of this non-wood forest product in Nordic countries, the ECODIVE project (Karelia CBC Programme) has researched forest vegetation and soil, producing an inventory of 68 edible wild plants and a study on soil types, to identify the most favourable sites for berry growth. The research has revealed that forest management and cuttings clearly influence the abundance of berries. “Forests should be managed so that not only trees, but also other plant species thrive – explains Maija Salemaa from the Natural Resource Institute of Finland, the project lead partner – Plant species create the basis for the diversity of the entire forest. Blueberries produce pie, but also support pollinating insects. Their presence has a comprehensive effect on the success of crops, and the sustainable development in the region”. Now, where do berries grow best, and why? Thanks to laser scanning, ECODIVE has identified in a scientific study the features of forests linked to locations of the highest berry yields. Prediction models have been developed to produce maps showing the most potential sites for bilberry picking. “In the future – says Päivi Merilä – models could be imported into forest planning systems, as we do for timber”. Today many owners start appreciating the multiple benefits of forests, including the non-wood products. Out of a population of 5,5 million people, Finland counts on 600.000 private forest possessors: if berry yields were to be integrated into forest planning, owners could evaluate a trade-off from loggings, when the moment comes to take decisions. “We need to change mentality – adds Hanna Leena Pesonen, sustainable development specialist – and to expand a global approach to forests as a source of timber and non-timber products, as biodiversity mines, as a resource for tourism and recreational activities”.

But whatever the use, today forest habitats are increasingly at risk because of climate change. Take fires, for example. They are not something unusual; on the contrary, for centuries Finnish forests have burnt. “Recurring fires used to play a key role in shaping the landscape of boreal forests – says Kaisa Junninen, senior advisor in species conservation for the Finnish state forestry company Metsähallitus – they are part of the normal dynamic of the ecosystem, creating diverse habitats and supporting the adaptation of the species. In a sense, fires bring a wealth of life to forests”. But the climate is changing, temperatures are rising, the last decade was the hottest on record and the warming estimated for the end of this century is +5° Celsius. Drier conditions can dramatically increase the risk of more frequent, severe, devastating wildfires. This looming challenge calls for new tools to monitor, forecast and possibly minimize the threats. And this is the aim of the BIOKARELIA project (Karelia CBC Programme), whose partners have used drones equipped with mobile laser scanners  or multi-spectral cameras, allowing to see “inside” forests, to collect and analyse data about trees, temperature, moisture. Through aerial (or terrestrial) laser scanning of digital data, the project has developed not only a platform for hosting and sharing spatial information, but also a mobile application able to forecast how fires can develop and spread, also considering meteorological conditions. “It is a valuable instrument to build models not only for preventive actions by property owners or authorities – says Tuomo Puumalainen, head of information services for the project partner Arbonaut – but also for real-time simulations, to plan evacuations, property protection, or other activities in response to an emergency, even using the mobile phone”. The ProMS Mobile application is available in Google Play for Android devices: a tool so significant that the Interreg Aurora Programme is considering taking it onboard for further development. At the same time, BIOKARELIA has given another push to sustain biological variability and ecosystems balance in forests, thanks to the biodiversity research & education platform, a multipurpose website where scientists can discover who is researching what and where, students can identify education opportunities in Finnish universities, and both categories can find out about funding sources for academic research activities. A precious networking and information tool for the knowledge of biodiversity experts, as well as for the sake of life variety on earth.

or multi-spectral cameras, allowing to see “inside” forests, to collect and analyse data about trees, temperature, moisture. Through aerial (or terrestrial) laser scanning of digital data, the project has developed not only a platform for hosting and sharing spatial information, but also a mobile application able to forecast how fires can develop and spread, also considering meteorological conditions. “It is a valuable instrument to build models not only for preventive actions by property owners or authorities – says Tuomo Puumalainen, head of information services for the project partner Arbonaut – but also for real-time simulations, to plan evacuations, property protection, or other activities in response to an emergency, even using the mobile phone”. The ProMS Mobile application is available in Google Play for Android devices: a tool so significant that the Interreg Aurora Programme is considering taking it onboard for further development. At the same time, BIOKARELIA has given another push to sustain biological variability and ecosystems balance in forests, thanks to the biodiversity research & education platform, a multipurpose website where scientists can discover who is researching what and where, students can identify education opportunities in Finnish universities, and both categories can find out about funding sources for academic research activities. A precious networking and information tool for the knowledge of biodiversity experts, as well as for the sake of life variety on earth.

“People are becoming more conscious about the environment – affirms Kalle Pakalén, project desk officer for the Interreg Northern Periphery and Arctic Programme – values are changing, the need to be in balance with nature is gaining momentum: a mere industry-dominated society has little future”. And as forest harvesting must be supported by science to be sustainable, at the same time technology is giving a big hand to forest management, even when it comes to unpaved roads. Accessibility is a key factor for the sector: roads are vital for timbers procurement, but they are equally important for villages inhabitants and livestock owners, for possessors of summer cottages and berry pickers. Finland can count on approximately 140.000 kilometres of forest roads: a huge, dense network to be kept clear from bushes and resting waters, with mild winters and rainy summers adding to the needs for maintenance. But how to prioritize it? Which renovation works should be taken forward by municipalities, and when? Traditional methods of collecting road data – by inspections and manual measurements – are laborious, costly and not accurate enough. The Access2Forest project (Karelia CBC Programme) has promoted the use of new technology to gather topographic information and to map unpaved forest roads, leading to efficient planning of maintenance. And here again, we are talking about remote sensing data: different road properties can be assessed through laser scanning, such as surface flatness, ditch quality, drying and water accumulation capacities, as well as vegetation on and beside roads. The result is the “digital twin” of a forest, with segments of routes coloured in their different (good or bad) conditions.

forest harvesting must be supported by science to be sustainable, at the same time technology is giving a big hand to forest management, even when it comes to unpaved roads. Accessibility is a key factor for the sector: roads are vital for timbers procurement, but they are equally important for villages inhabitants and livestock owners, for possessors of summer cottages and berry pickers. Finland can count on approximately 140.000 kilometres of forest roads: a huge, dense network to be kept clear from bushes and resting waters, with mild winters and rainy summers adding to the needs for maintenance. But how to prioritize it? Which renovation works should be taken forward by municipalities, and when? Traditional methods of collecting road data – by inspections and manual measurements – are laborious, costly and not accurate enough. The Access2Forest project (Karelia CBC Programme) has promoted the use of new technology to gather topographic information and to map unpaved forest roads, leading to efficient planning of maintenance. And here again, we are talking about remote sensing data: different road properties can be assessed through laser scanning, such as surface flatness, ditch quality, drying and water accumulation capacities, as well as vegetation on and beside roads. The result is the “digital twin” of a forest, with segments of routes coloured in their different (good or bad) conditions.

“When roads can be digitally illustrated – says Mika Nousiainen, expert of the Finnish Forest Centre, a project partner – municipalities or other funding agencies can get a reliable overview of what is necessary to repair and are able to prioritise interventions”. It could well be that a main logging trail is in good shape, but a nearby village road has been converted into a muddy field and badly needs restoration. Even though the project’s implementing time has come to an end, the legacy of Access2Forests is passing on, and results are being now used by two other development projects: “New digital solutions in predicting the trafficability of forest roads”, funded by North Karelia structural funds with support from the EU; and “Securing wood and energy supply”, backed by the Finnish Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry. “The production and utilization of digital forest information has enormous potential – concludes Timo Tahvanainen, development manager for the lead project partner Business Joensuu – We continue to work on this subject with a wide group of companies, researchers, and application developers”.

To conclude, forest land is indeed a complex ecosystem, with many different purposes. If in the past it was mostly about paper and wood products industry, today new needs have emerged, from carbon bonding to biodiversity maintenance. Diversified, carefully planned uses of forests reflect the increasing efforts towards nature conservation, and computer technologies are making all the difference: through their various, multifaceted approach, ENI CBC programmes have contributed to this challenge. Valuable neighbouring relations and partnership principles were shattered by the Russian aggression against Ukraine, but most of the projects were able to readapt, sometimes finetuning their activities, sometimes identifying new purposes. Overall, they have continued developing approaches and tools for a variety of initiatives throughout arctic regions, from quality control of soil preparation to road maintenance planning, from trees protection to climate change mitigation measures. It’s all about good forest management decisions, and results are ripe to be taken onboard. Programmes such as Interreg Aurora and Interreg Northern Periphery and Arctic Programme – carriers of a plurality of perspectives and competences – are ready to do it. Regional authorities have also expressed their interest and could invest in the work initiated, in the capacities spread. The heritage of the Northern ENI CBC programmes is there to stay, in the pursuit of solutions to balance the function of boreal and Arctic forests: a legacy which is a step towards the responsible use of Nordic woodlands.