Towards a circular economy in the South

How can waste reprocessing favour a circular economy and a sustainable future? Environmental considerations are at the forefront of Interreg NEXT priorities: regulations ask all programmes to devote 30% of the budget to contribute to climate targets. But making use of waste to promote a green, circular economy was also high on the agenda of ENI CBC: at the end of the programming cycle, it turns out that research was key to waste reconditioning, and it has favoured innovative solutions which are now opening market opportunities and boosting employment. The idea of a system where materials never become waste, is gaining space.

We have decided to reach the southern shores of the Mediterranean to report on how ENI CBC projects have impacted on the issue of solid and water waste transformation, and what legacy they are leaving behind for Interreg NEXT to build upon. We have chosen Tunisia for our mission, a country which strongly believes in the value of cross-border cooperation with the EU, and which joined CBC since its establishment in 2006. A country where two ENPI, then ENI, now Interreg NEXT programmes were (and are) active, the Mediterranean Sea Basin (MSB) and Italy-Tunisia. In this area, as in the rest of the Mediterranean, an intense human activity – tourism to begin with – results in an increasing demand for material resources, in the growing consumption of energy and water, and the consequent production of solid and water waste. A strong potential of natural resources is being threatened by the side-effects of growth. All good reasons for cross-border cooperation programmes to bring partners together and start working. “If we compare the previous two programming cycles – says Samira Rafrafi, director at the Ministry of Economy and Planning in Tunis – we notice a very positive evolution of our participation at this European cooperation framework: the number of Tunisian partners in MSB, for example, went up from 60 to 89. And the budget for Tunisia increased from 10% to 14%, a sign that we are really progressing. Also considering a bilateral programme like Italy-Tunisia, it’s remarkable that we have reached 13 leading partners out of 28 projects: this really reflects the experience of stakeholders – continues Rafrafi – who are now ready to embark on a new adventure called Interreg NEXT”.

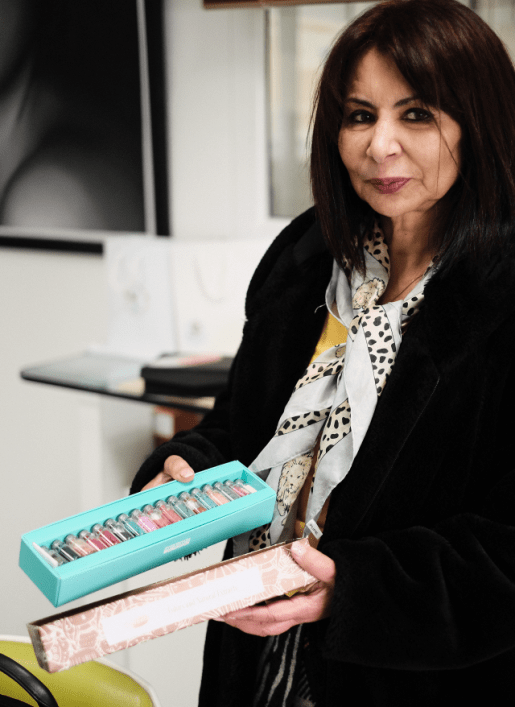

In this new adventure, there is a lesson from the past to be inherited for a greener Mediterranean: turning pollutants into valuable resources is a good incentive for recycling. The challenge now is to speed up the transition and to move from a pure waste management approach to a circular economy approach. “Tunisia considers circular economy a strategic drive – continues Rafrafi – and we have prepared our legislation well so that we can fully embrace it. Many projects illustrate these efforts, whether from the Mediterranean Sea Basin (MSB) or in the Italy-Tunisia Programme”. Let’s take for example BESTMEDGRAPE (MSB): here you have grape waste turned into health or beauty products. The process is simple. Wine-making generates large quantities of waste products. After the grapes are squeezed, about 20 percent of their weight remains in the form of skins, seeds, and stems: it is called pomace, and the wine industry produces a lot of it. Its antioxidant properties have been known for ages, but today science allows the  creation of new pharmaceutical products out of it. How? “During the first phase of the project it was the scientists who researched the bioactive components of wine by-products, looking for antioxidant and anti-inflammatory microparticles – says Boutheina Gharbi, project manager – This knowledge was then transferred into manufactured products”. The second stage of the project involved setting up new companies to commercialise the various products. Each of the five participating countries – Tunisia, Italy, France, Lebanon and Jordan – selected 30 potential entrepreneurs, who attended scientific training sessions in laboratories, as well as business-creation seminars to understand how to set up a small company. They had to learn not only how to turn pomaces into beauty creams, but also how to stay afloat on the market. Twenty living laboratories were activated, and four brevets obtained on the characterisation and extraction of local grape varieties. Ten new products have been developed by BESTMEDGRAPE for marketing purposes. And out of the 150 trainees, 50 were selected to receive grants and to establish their own business. “Activities have involved local farms and wineries, SMEs and researchers – continues Gharbi – but for the selection of new entrepreneurs we have targeted mostly youth and women, to boost local economy while supporting social inclusion”. Today, the sustainable exploitation of winemaking-waste has led to the creation of the first 40 start-ups in the

creation of new pharmaceutical products out of it. How? “During the first phase of the project it was the scientists who researched the bioactive components of wine by-products, looking for antioxidant and anti-inflammatory microparticles – says Boutheina Gharbi, project manager – This knowledge was then transferred into manufactured products”. The second stage of the project involved setting up new companies to commercialise the various products. Each of the five participating countries – Tunisia, Italy, France, Lebanon and Jordan – selected 30 potential entrepreneurs, who attended scientific training sessions in laboratories, as well as business-creation seminars to understand how to set up a small company. They had to learn not only how to turn pomaces into beauty creams, but also how to stay afloat on the market. Twenty living laboratories were activated, and four brevets obtained on the characterisation and extraction of local grape varieties. Ten new products have been developed by BESTMEDGRAPE for marketing purposes. And out of the 150 trainees, 50 were selected to receive grants and to establish their own business. “Activities have involved local farms and wineries, SMEs and researchers – continues Gharbi – but for the selection of new entrepreneurs we have targeted mostly youth and women, to boost local economy while supporting social inclusion”. Today, the sustainable exploitation of winemaking-waste has led to the creation of the first 40 start-ups in the  Mediterranean. Amal Trabelsi was 19 and still at university when she joined BESTMEDGRAPE: now 22, she met her working partners during the project, and they have just set up their own company in Bizerte. “I am a nutritionist, and the other girls are engineers. After the training we decided to create our brand “Vitofera” and open a small business together. We produce grape seed oil, it’s rich in antioxidants, it moisturises the skin, it’s very good for the hair, the face, and the whole body. Now we must find a market, but I am confident that we will”.

Mediterranean. Amal Trabelsi was 19 and still at university when she joined BESTMEDGRAPE: now 22, she met her working partners during the project, and they have just set up their own company in Bizerte. “I am a nutritionist, and the other girls are engineers. After the training we decided to create our brand “Vitofera” and open a small business together. We produce grape seed oil, it’s rich in antioxidants, it moisturises the skin, it’s very good for the hair, the face, and the whole body. Now we must find a market, but I am confident that we will”.

From grapes to body oil; from crab shells to food supplements. In Tunisia – as well as in all other countries bent on the Mediterranean – sea currents accumulate different sediments on harbour bottoms, making it difficult for boats to dock at certain times. Dredging is an essential technique to maintain proper water depths in fishing ports and bays. Dredged sediments – among which are seagrasses – are considered toxic waste, due to their significant amounts of metals and other pollutants, and therefore they need to be treated before being disposed of. And that is not the only issue affecting the Mediterranean ports. The fish industry – often installed around fishing harbours – has seen a strong increase, driven by the development of technologies and by worldwide recognition of fish as a key component of a healthy, balanced diet. Modern seafood processing practices result in amassment of a large volume of waste products, like head, tails, shells, backbones: at world level, it is estimated that about two-thirds of the total amount of fish is discarded as waste, creating strong environmental concerns. But scientists have discovered that seafood waste may incorporate high-value products: for example, shellfish contains a good amount of chitin, a chemical compost precious for its biocompatibility, and for its antitumor, antimicrobial and antioxidant activities. There is commercial value to be gained from fish by-products, all the more reason to consider the disposal and recycling of these wastes as a key issue to be addressed.

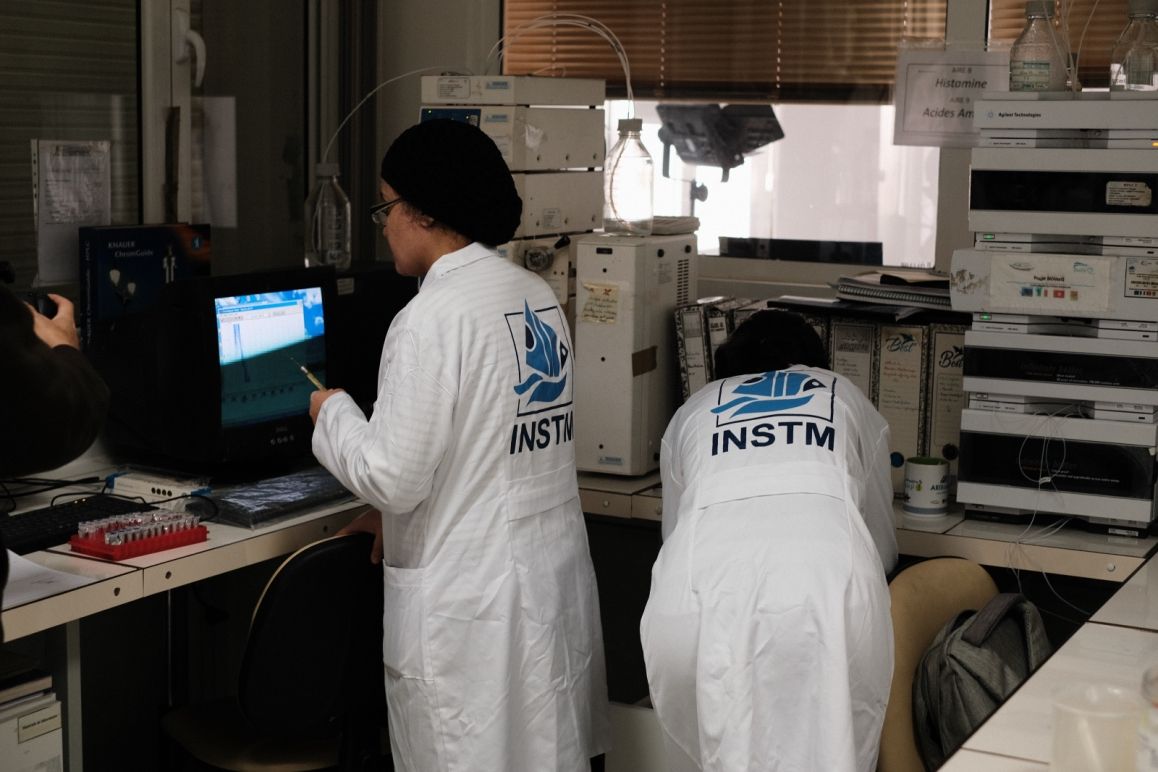

Which is what ARIBIOTECH (Italy-Tunisia) is doing. The project promotes the treatment and valorisation of seafood waste and dredging sediments, turning them into organic packaging or dietary  supplements. “We are the continuation of Biovec – explains the coordinator, Saloua Sadok, head of the laboratory Blue Biotechnology & Acquatic Bioproducts in Tunis – a previous ENPI CBC project which focused on the production of paper from the treatment of algae waste. In the same spirit, we have persisted in our work on waste recovery”. There has been extensive laboratory analysis and work on methods of extracting chitin from marine waste resources. After a good deal of research, a new plant has been set up to treat organic waste from Tunisia’s shellfish processing companies, which are located all around the country’s 41 fishing ports. At the end of the process, crab or crevette shells are transformed into a biofilm for food packaging, a natural coating which slows down water loss and oxidation of food; or into a powder to be used as a complementary food supplement. But what about the sediments dredged from the seabed? “We have focused on the waste of

supplements. “We are the continuation of Biovec – explains the coordinator, Saloua Sadok, head of the laboratory Blue Biotechnology & Acquatic Bioproducts in Tunis – a previous ENPI CBC project which focused on the production of paper from the treatment of algae waste. In the same spirit, we have persisted in our work on waste recovery”. There has been extensive laboratory analysis and work on methods of extracting chitin from marine waste resources. After a good deal of research, a new plant has been set up to treat organic waste from Tunisia’s shellfish processing companies, which are located all around the country’s 41 fishing ports. At the end of the process, crab or crevette shells are transformed into a biofilm for food packaging, a natural coating which slows down water loss and oxidation of food; or into a powder to be used as a complementary food supplement. But what about the sediments dredged from the seabed? “We have focused on the waste of Posidonia Oceanica, the sea grass endemic to the Mediterranean – Sadok continues – and we have transformed this biomass into aerogels, which are good for cosmetic purposes”. Again, as in the case of the wine by-products, a discarded biomass is transformed into high-value products: a key concept of a circular economy, which reduces the consumption of raw materials and increases the influx of renewable resources. A concept Interreg NEXT is receiving from ENI CBC projects, to keep developing upon.

Posidonia Oceanica, the sea grass endemic to the Mediterranean – Sadok continues – and we have transformed this biomass into aerogels, which are good for cosmetic purposes”. Again, as in the case of the wine by-products, a discarded biomass is transformed into high-value products: a key concept of a circular economy, which reduces the consumption of raw materials and increases the influx of renewable resources. A concept Interreg NEXT is receiving from ENI CBC projects, to keep developing upon.

Take food, for example. About a third of the food produced around the world goes to waste, and much of it ends up in landfills. Hotels, schools, households, markets, they all produce tons of biodegradable materials that once buried are unable to decompose properly because of poor ventilation, temperature, and humidity conditions. Once in landfills, biowaste becomes a source of methane, a greenhouse gas stronger than carbon dioxide. But if these food, yard, animal and agricultural waste are piled up in the open and allowed to decompose under controlled conditions, they can reduce their environmental impact and extract their potential value. It’s called compost, and farmers refer to it as “black gold”. As  with wine by-products and marine waste, composting can turn biowaste into a nutrient-rich soil that helps plants thrive. And here is SIRCLES (MED), a project creating new jobs by applying the circular economy model to the organic waste sector. “In Tunisia, organic waste is not yet sorted – says the project manager Aymen Louhichi – so we do it ourselves, we bring the waste to our pilot farm, we make our compost by adding some manure and green waste, and then we sell it as natural fertiliser”. Within the project – and adapting every initiative to the local contexts – seven pilot sites have been established, one for each participating country (Tunisia, Spain, Greece, Italy, Lebanon, Palestine and Jordan). Project partners have organised trainings in bio-waste management and circular economy practices, giving preference to NEETS and women in the selection process, and indeed 38% of the 286 trainees

with wine by-products and marine waste, composting can turn biowaste into a nutrient-rich soil that helps plants thrive. And here is SIRCLES (MED), a project creating new jobs by applying the circular economy model to the organic waste sector. “In Tunisia, organic waste is not yet sorted – says the project manager Aymen Louhichi – so we do it ourselves, we bring the waste to our pilot farm, we make our compost by adding some manure and green waste, and then we sell it as natural fertiliser”. Within the project – and adapting every initiative to the local contexts – seven pilot sites have been established, one for each participating country (Tunisia, Spain, Greece, Italy, Lebanon, Palestine and Jordan). Project partners have organised trainings in bio-waste management and circular economy practices, giving preference to NEETS and women in the selection process, and indeed 38% of the 286 trainees were female, demonstrating the project’s commitment to inclusivity and women’s empowerment. Moreover, 166 trainees have been employed by the pilot sites themselves. “We have worked hard to establish a public-private partnership and to enable a recognised certificate to follow the training – continues Louhichi – In Tunisia, we have managed to give out 121 certificates, so these young people now have an official title to work in composting or organic farming”.

were female, demonstrating the project’s commitment to inclusivity and women’s empowerment. Moreover, 166 trainees have been employed by the pilot sites themselves. “We have worked hard to establish a public-private partnership and to enable a recognised certificate to follow the training – continues Louhichi – In Tunisia, we have managed to give out 121 certificates, so these young people now have an official title to work in composting or organic farming”.

Nowadays farmers are reverting to the application of compost to replace chemical fertilisers and to restore soil fertility. But turning to natural solutions is also a recipe for the treatment of water waste, especially in drought prone regions such as the Mediterranean, where innovative, low-cost technologies are today used to recycle non-conventional water resources for domestic purposes. “Water can be used more than once, provided that, after is it used, it is returned to the environment with such a quality that others can use it again – says Latifa Bousselmi, professor at the Water Research and Technology Centre (CERTE) in Tunis and project manager – This is what the NAWAMED project does: “it takes grey waters, it treats them, and reuses them. And this is achieved through a living green wall, a wall covered with plants inserted in the urban setting”. In the framework of the MSB, eight such pilot sites have been implemented throughout the Mediterranean, in Tunisia, Jordan, Lebanon, Malta and Italy. In Tunis, the partners take water from the showers of a university campus in El Menzah, near CERTE, filter it through a green wall of plants, and then reuse it to flush toilets and to water gardens and fruit trees. “The cleansing process takes place at the level of the plant’s roots – explains Ahmed Ghrabi, director of the Centre – Once micro-organisms develop with the supply of oxygen, they purify the water and break down all the pollutants. At that point the recycled water can be reused”. The project also collects rainwater from the roof of the university building, so that it can be filtered and reused to keep the system running during the summer, when grey water is unavailable because the students are at home. And there is more than water treatment: the green living wall absorbs CO2, reduces the local temperature, favours biodiversity. It is a “multifunctional system”, which has brough together a team of scientists, botanists, civil engineers, water experts and architects, and where the wall is just the upper part of the iceberg. “All water actors worked hard together to adapt the living wall concept to the context – continues Bousselmi – They have considered all possible implications, from the legal to the economic point of view, to make it a durable and sustainable solution: and now they have developed a know-how essential for the multiplication of the system”.

that point the recycled water can be reused”. The project also collects rainwater from the roof of the university building, so that it can be filtered and reused to keep the system running during the summer, when grey water is unavailable because the students are at home. And there is more than water treatment: the green living wall absorbs CO2, reduces the local temperature, favours biodiversity. It is a “multifunctional system”, which has brough together a team of scientists, botanists, civil engineers, water experts and architects, and where the wall is just the upper part of the iceberg. “All water actors worked hard together to adapt the living wall concept to the context – continues Bousselmi – They have considered all possible implications, from the legal to the economic point of view, to make it a durable and sustainable solution: and now they have developed a know-how essential for the multiplication of the system”.

Fostering the inclusion in national policy frameworks of waste & water treatment and reuse techniques, was among the objectives of many ENI CBC projects. The idea to take biomaterials from the earth and make them re-enter in the economy at the end of their living/using cycle, is inherited and remains in the NEXT programming cycle. Today, Interreg programmes keep offering the ideal structure to face global issues by sharing experiences from multiple partners across external borders; they also provide the financial support needed to develop research ideas and to move them from the prototype stage to the demonstration stage, with a view to wider adoption. MSB and Italy-Tunisia have well seeded the ground, and the legacy is clear: reuse, remanufacture, recycle, compost is the way to go ahead in the future. And if the elimination of waste and pollution is the first principle of a circular economy, there is a lot of work on the way.